Recent LLM systems increasingly get better long-horizon behavior by wrapping the model in an iterative agent loop (retrieve/compute/write state → re-prompt) rather than trying to fit all required information into one prompt. This “recursive outer-loop” framing is a practical response to two issues with very large context windows:

Approaches like Recursive Language Models (RLMs) [citation] represent a shift from “one-shot” inference to “programmatic recursive inference.”

A common baseline for “hard” tasks is still one-shot prompting: concatenate large amounts of text/code into the prompt and rely on attention to surface what matters [citation] . That approach pushes both compute and memory bandwidth: attention has unfavorable scaling with sequence length and repeatedly reads the accumulated KV-cache during decoding, so longer prompts increase per-token work and memory traffic [citation] . Empirically, more context is not automatically more usable; long-context evaluations show strong position effects (“lost in the middle”), which is one concrete reason large prompts can feel brittle even when the answer is present.

A “single huge prompt” behaves like a flat memory model: everything is placed in the same addressable space (the attention window) and is in principle accessible at each decode step. In practice, this is expensive (sequence-length scaling + KV-cache traffic) and reliability-limited (attention does not allocate capacity uniformly across positions). A recursive outer-loop makes the hierarchy explicit by splitting active working set from backing store:

L1 (active context): the bounded prompt window + KV-cache that the model attends over at low latency.

The trade-off is straightforward: the system pays additional round-trip latency and extra LLM calls, but it can keep the hot context small and targeted, which tends to improve robustness on long tasks compared with “stuff everything into the prompt.”

For years, the dominant approach to reasoning has been to blindly scale the context window: stuffing (chunked/summarized/RAGed) megabytes of documents, codebases, and history into a single prompt. This is the “unified memory” model: fast, but brittle, and prone to “context rot.”

Systems like RLM [citation] propose a different path: treating context not as a stream of tokens to be consumed, but as an external variable handle. In this paradigm, the model is given a “working memory” (the prompt) and access to “external memory” (the REPL variables). It programmatically queries, searches, and decomposes this context using code and recursive sub-calls.

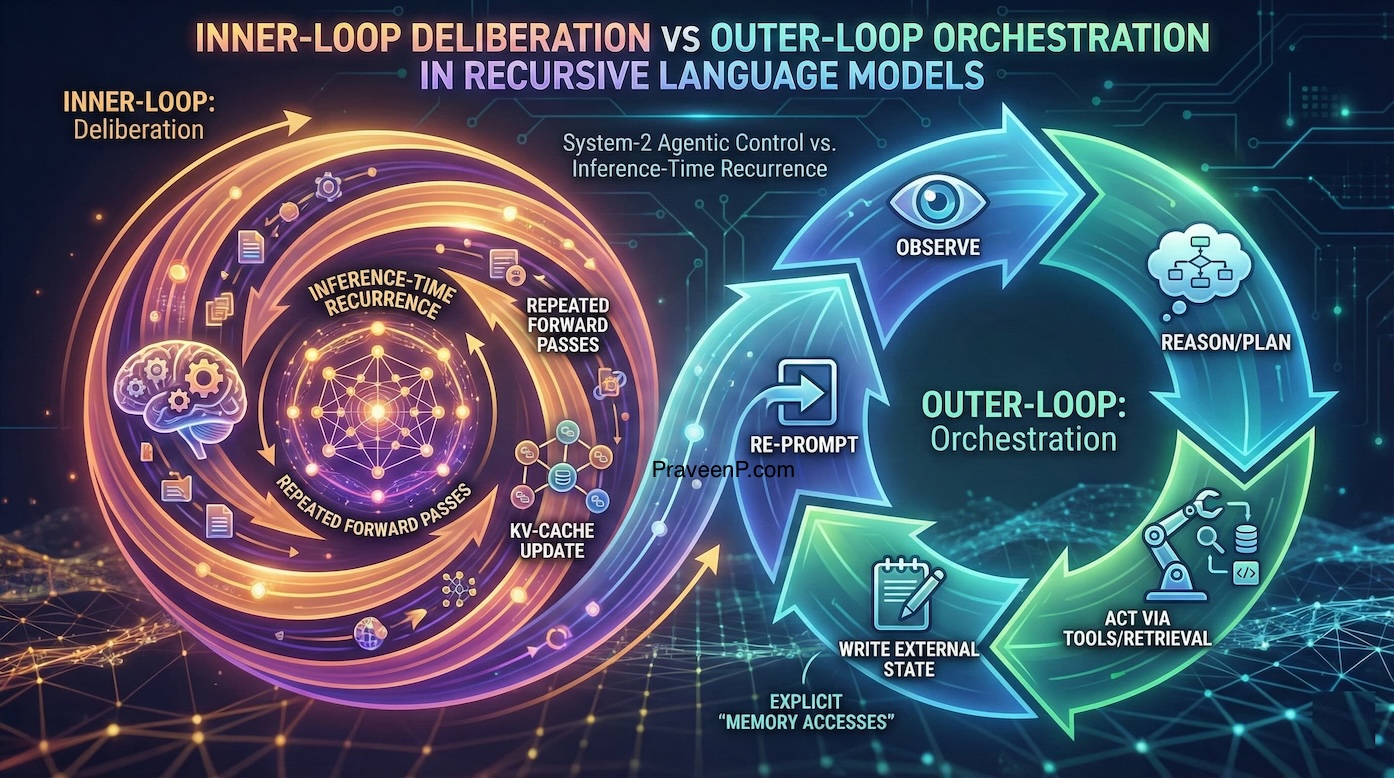

This is part of a larger trend where AI system design is separating into two distinct feedback loops, optimizing for different sets of constraints and objectives.

This is the inference-time recurrence of an autoregressive transformer: repeated forward passes that update internal state (KV-cache, residual stream) as tokens are generated. It corresponds to fast pattern completion (System 1) and—when extended with extra test-time compute—approaches slower System 2, increasingly via hidden or compact reasoning rather than always-visible Chain-of-Thought [citation] .

Autoregressive “thinking” is inference-time recurrence: Each decoded token triggers a new transformer forward pass that reads the accumulated KV-cache and appends fresh keys/values, so additional test-time compute is realized as more decode steps (and therefore more KV reads/writes) rather than literal recursion within a single pass. [citation]

Long-context behavior is not uniformly reliable: even when relevant evidence is present in the prompt, accuracy can degrade when that evidence is positioned far from the ends of the sequence (the “lost-in-the-middle” effect), which is a concrete mechanism behind perceived context degradation at scale. [citation]

When “System-2-like” behavior is induced, it increasingly need not correspond to verbose, user-visible chain-of-thought; hidden/compact deliberation approaches attempt to preserve multi-step reasoning signal while compressing or internalizing intermediate reasoning states during decoding. [citation]

Inner-loop recurrence provides extremely low-latency pattern completion because all computation stays on-device within a tight decode loop over a bounded active context (prompt + KV-cache), enabling high-throughput token generation when the hot working set fits the memory hierarchy well. [citation]

IO-aware attention implementations reduce the effective memory traffic of attention by restructuring reads/writes to better match GPU memory hierarchies, improving realized throughput for long sequences without approximating attention semantics. [citation]

Hidden/compact reasoning techniques can reduce exposure of intermediate reasoning traces while still providing a mechanism for multi-step refinement at inference time, which can be useful for both efficiency and governance constraints around revealing intermediate thoughts. [citation]

The hot working set is strictly bounded: KV-cache grows with sequence length and must be consulted every step, so context length and deliberation depth translate directly into higher bandwidth pressure and latency per generated token. [citation]

Long-context reliability failures (e.g., lost-in-the-middle) imply that “just add more tokens” is not a monotonic scaling strategy; beyond capacity/bandwidth costs, effective utilization can degrade due to model positional biases and retrieval inefficiency inside attention. [citation]

Compact/hidden deliberation schemes introduce their own failure modes (e.g., dependence on auxiliary latent representations and decoding procedures), shifting complexity from user-visible text to model-/system-level protocols that must be validated under distribution shift. [citation]

Advanced packaging is a first-order limiter: The practical “inner-loop size” is gated by how much high-bandwidth memory can be co-packaged and coherently accessed at speed-constraints that show up as supply/complexity bottlenecks beyond raw logic-node shrink.

This is the System 2 orchestration layer: an agentic/REPL-style loop that treats the LLM as a fixed-weight “reasoning core” and composes tools, retrieval, and state management around it. The outer loop expands capability by paging information into the inner loop on demand, rather than trying to make the inner loop hold everything at once [citation] .

The outer-loop is a System-2 orchestration layer that wraps the LLM in an agentic control cycle (observe → reason/plan → act via tools/retrieval → write external state → re-prompt), effectively turning tool calls and state updates into explicit “memory accesses” that feed the inner-loop only what is currently needed. [citation]

Tool use can be integrated as a learned policy: models can be trained (or self-trained) to decide when to call external APIs and how to incorporate returned values into subsequent generation, making “fetch” operations a first-class computational primitive rather than an ad hoc wrapper. [citation] [citation]

External-memory managers can implement OS-like policies for what stays in-context vs. what gets evicted, summarized, or retrieved later (“virtual context”), treating the prompt window as a scarce cache and external stores as a larger address space. [citation]

Outer-loop recursion converts unbounded information needs into bounded-context interactions by demand-loading only task-relevant slices, which can improve long-horizon correctness when combined with strong retrieval, caching, and verification policies. [citation]

By delegating structured computation to tools (code execution, search, solvers), the system can replace fragile pure-text reasoning steps with verifiable intermediate artifacts, and ReAct-style interleavings provide a simple template for this synergy. [citation]

At the serving/runtime layer, paging-like KV allocation mechanisms (e.g., PagedAttention) improve utilization and multiplexing across requests by managing KV memory as paged blocks rather than monolithic contiguous buffers, aligning LLM serving more closely with virtual-memory design. [citation]

The outer loop is latency-dominated: each “page-in” (retrieval/tool call) introduces microsecond–millisecond (or worse) round-trips, so end-to-end performance depends on cache hit rate, batching, and minimizing the number of outer iterations. [citation]

Correctness becomes policy-sensitive: failures shift from “model forgot” to “retrieval/tooling selected the wrong evidence or executed the wrong action,” so evaluation must cover the combined system (retriever + tool APIs + controller + LLM). [citation] [citation]

Virtual-context approaches require robust summarization, indexing, and eviction strategies; otherwise the system either thrashes (too many fetches) or accumulates low-quality compressed state that poisons future prompts. [citation]

What excites me most involves lifting the “attention control” out of the implicit weights and into the explicit action space of the agent.

grep "error" logs.txt), and effectively infinite.By using RL to train these Outer Loops, we teach models how to manage their own attention economy. The act of “reading a file,” “grepping a log,” or “calling a sub-model” becomes a discrete action in an RL trajectory [citation] . This orchestrates the raw, expensive “intelligence” of the Inner Loop with the vast, cheap “memory” of the Outer Loop.

The RLM-style Outer-Loop pattern unlocks several high-value applications that were previously impractical or insecure with flat-context models:

For autonomous software engineers (like Devin, Cursor’s Agents, etc.), the Outer-Loop is critical. You cannot fit an entire legacy codebase into a prompt. An RLM-based agent can recursively “explore” the directory structure, “grep” for usages, and “read” only the relevant files, mimicking how human engineers navigate large codebases.

The RLM pattern naturally supports “heterogeneous compute” and data types that defy tokenization. Instead of trying to tokenize a massive 3D point cloud or a high-framerate video stream, the RLM can treat these as variables (handles) in its environment.

In these RLM-style Outer Loops, because the “reasoning” happens in a REPL, we can run that REPL inside a Trusted Execution Environment (TEE), while the model orchestrator remains outside.

fhe_add(encrypted_tensor_a, encrypted_tensor_b)). The model reasons about how to process the data, while the cryptographic primitives execute the math blindly on encrypted ciphertext. This enables “Confidential AI” where the model provider never sees the user’s data.We will likely see a split in model specialization.

As noted by Prime Intellect, there is a push to reduce the “multiplicative depth” of recursive calls [citation] . We may move from explicit Python REPLs (which have parsing overhead) to latent-space REPLs, where the “program” and “variables” are represented in high-dimensional vectors, and the “execution” happens via specialized neural modules rather than a Python interpreter.

The “Outer Loop” paradigm effectively uncaps the “test-time compute” budget. If a problem is hard, the model can simply iterate longer in the outer loop—searching more files, running more simulations, calling more sub-models—without being constrained by the fixed forward-pass depth of the neural network. This turns “intelligence” into a resource we can purchase with time and electricity, decoupled from semiconductor node scaling.

The “Recursive Outer-Loop” paradigm is a necessary evolution. It acknowledges that while silicon scaling (Inner Loop) is met with physics-based friction, system architectural scaling (Outer Loop) is filling in the gaps to make infinite context with agentic memory a reality sooner.

Systems that decouple “context storage” from “reasoning capacity,” allow us to build agents that don’t just process tokens, but navigate information. As we move toward agents that run for weeks or months, the ability to programmatically manage state—to decide what to remember, what to forget, and where to look—will be the defining characteristic of intelligence.